The U22 Tradeoff

How do U22 Initiative players perform in their first season? What about later years? And what factors shape those trajectories?

Earlier this year, Ben Wright and Arman Kafai each examined the U22 Initiative, one of MLS’s most valuable mechanisms. Ben outlined its objectives and evaluated its impact on and off the field. Arman went more granular, tallying the minutes each club’s current U22 Initiative players have logged since 2021. Both pieces are worth your time, especially if you’re unfamiliar with the mechanics of the initiative.

Rather than revisit ground they’ve covered, I wanted to take a different angle, one focused on the tradeoffs baked into the U22 gambit. While the mechanism offers cap flexibility and opens the door to high-upside acquisitions, it has yet to yield consistent returns, prompting me to explore whether certain factors contribute to more favorable outcomes.

Of course, because it’s MLS, there are limitations to this analysis. Chief among them: although the U22 Initiative launched in 2021, the club roster profiles didn’t debut until 2024, leaving no public record of when players were designated as U22s.

Partly for that reason, I didn’t feel confident using the same method to calculate U22 minutes as I did supplemental roster minutes for my last blog. More importantly, though, I didn’t think it mattered whether a U22 Initiative player was bought down with allocation money or reclassified as a Designated Player (DP); if he was brought to the league (or re-signed) via the U22 Initiative, his contributions over time still reflect the initial investment. In many cases, designations change as mere accounting tactics.

Take Real Salt Lake, for example. The Claret and Cobalt had two DPs and three U22s prior to signing Diego Luna to a contract extension in March 2024. To minimize the cap impact of Luna’s base salary increase (from $120,000 in 2023 to $400,000 in 2024) while remaining compliant, the club restructured its roster, as outlined in the press release:

Luna… is now considered a U22 roster designation for RSL, joining Braian Ojeda and Nelson Palacio. RSL winger Andrés Gómez [who had occupied a U22 slot] is moved into the ‘Young DP’ slot, alongside Chicho Arango and newcomer Matt Crooks (TAM-able in MLS’ secondary window this summer).

These moves brought Luna and Gómez’s combined budget charge to just $400,000 — the minimum amount Luna alone would’ve hit the cap without the U22 slot. Factor in bonuses and any due installment of his reported $250,000 transfer fee, and the value of RSL’s maneuvering becomes clear.

That brings us back to the core questions driving this analysis. How do U22 Initiative players perform in their first season? What about later years? And what factors shape those trajectories?

Before getting into the numbers, some notes on methodology:

By my count, nine players, including Marcos López (San Jose Earthquakes) and Diego Palacios (LAFC), joined the league before 2021 and were later reclassified as U22s. For this analysis, I treated 2021 as their first year under that designation and noted that each had prior MLS experience.

Thirty-six U22 Initiative players were brought to the league during its summer transfer window. To mitigate bias introduced by their midseason arrivals, I doubled their first-year minutes — an imperfect but rational approach.1

Percentages of available minutes are based on the average number of regular season minutes played by MLS clubs from 2021 to 2024: 3,398, per American Soccer Analysis.

Also worth noting: only players who logged at least one regular season minute in a given year are included in the averages below. Players who did not feature due to injury, loan, or other reasons were excluded, with their minutes left blank to avoid skewing the results.

Erik López, for example, joined Atlanta United’s first team in January 2021, logging 960 minutes that year. He was loaned to Club Atlético Banfield of the Argentine first division the following season and did not appear in MLS play. As a result, his Year 2 value is blank in the dataset. He returned in 2023 and recorded 28 minutes before his contract was terminated that August, marking the end of his third and final season as a U22.

By my count, López is one of 118 players to occupy a U22 slot between the initiative’s launch in 2021 and the end of the 2024 regular season. All but nine logged at least one league minute in their first year as a U22. From there:

71 of the 92 players eligible for a second year (i.e., excluding 2024’s first-time U22s) appeared in Year 2;

41 of the 65 players eligible for a third year featured in Year 3;

And just 13 of the 38 players believed to have been U22s in 2021 remained in the league and saw the field in 2024.

These numbers serve as reminders that 1) acquisitions involving young players carry amplified risk, and 2) even with four years of data, the sample size remains small.

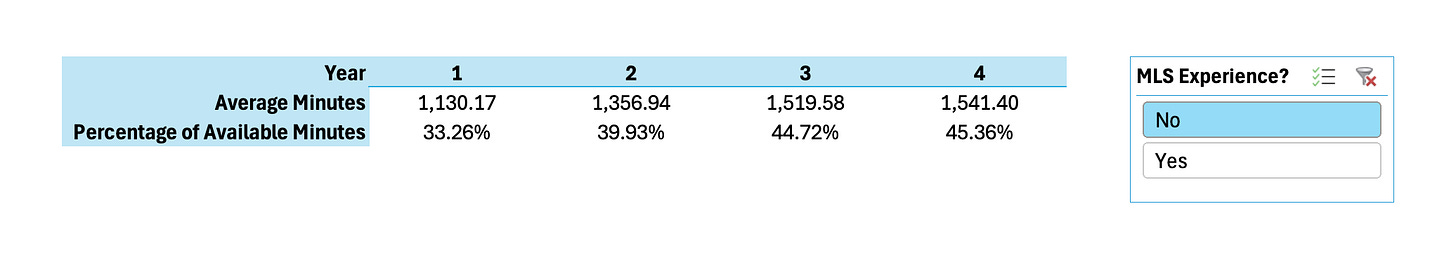

With that in mind, U22 Initiative players average 1,279 minutes — or roughly 38% of the available total — in their first season under that designation. That figure rises modestly in Year 2 and again in Year 3, but even then, the average U22 logs less than half of the possible minutes:

That may seem underwhelming considering the level of investment — in his piece for Backheeled, Ben noted that the average incoming transfer fee for a U22 is $1.9 million — but it’s consistent with the approach taken by Atlanta United President and CEO Garth Lagerwey, among others.

“We look at those U22 spots as key depth,” Lagerwey told Jason Longshore in August. “I think it’s misleading to describe them as starters. They could be starters, [and] we hope they become that, but a lot of times, when they’re starting out, in particular, they’re going to be key reserves.”

Still, these averages tell just part of the story. Another key component is age.

Among the top 30 U22s in first-year minutes, just three were 20 or younger during the league year: Julian Araujo (first, 3,056 minutes), Tomás Avilés (20th, 972 minutes, prorated to 1,988), and Cade Cowell (30th, 1,697 minutes). That distribution may not be surprising, but it reflects a trend that perhaps is: U22s who enter the league (or sign extensions) at younger ages don’t just earn fewer minutes in Year 1 than those who arrive at 21 or older; they contribute less in later seasons, too.

In other words, the adjustment curve for younger U22s is not just steeper — it’s longer.

Equally, if not more important than age is league experience. Thirteen of the top 30 had played in MLS before assuming their U22 designations, including Araujo and Aidan Morris (2,861 minutes), who ranked first and second, respectively. Eight of those 13 came through the academy pipeline, while the other five joined the league before 2021 and were reclassified as U22s following the initiative’s launch.

On average, players with league experience log 1,808 minutes in their first season as a U22, compared to 1,130 for those without. That’s a 678-minute difference, or roughly 20% of the regular season.

The gap narrows but remains noticeable in Years 2 and 3:

Different combinations of age and league experience magnify the disparities in on-field contributions. Perhaps most notably, U22 Initiative players who enter MLS at age 20 or younger without prior league experience average just 802 minutes in their first season, less than a quarter of the available total:

That’s not to dissuade clubs from using a U22 slot on, say, a 20-year-old Colombian, though. After all, the initiative reflects a broader shift aimed at improving MLS’s position in the global market by creating more avenues to acquire high-upside prospects who can later be flipped for a profit.

That leads us to the off-field returns. By my count, 31 U22 Initiative players have been transferred outside the league, with just 12 of those sales involving players who were 21 or younger at the time of their departure. Yet, using Ben’s data, those 12 players generated $82.36 million in outgoing transfer fees, or more than 65% of all U22-related revenue.

Just one player aged 22 or older has commanded an eight-figure fee (Santi Rodríguez, whom New York City FC sold for a reported $17 million in February), compared to four players aged 21 or younger. The next highest fee among the older group was for Cristian Olivera, who, like Rodríguez, moved to Brazil, but for just a quarter of the price.

Among the 12 players transferred at age 21 or younger, the average time between their arrival (or contract extension) and departure was 597 days — just over a year and a half. Efraín Álvarez led the group in tenure, remaining with the LA Galaxy for 785 days after signing his extension, while Jhon Durán earned the quickest move abroad, departing just 381 days after joining the Chicago Fire in January 2022.

Notably, Durán remains the youngest U22 Initiative player to be transferred, garnering what has since become a league-record outgoing fee:

That’s no coincidence. Sure, the fee might be an outlier. But the nature of the move, particularly its timing, reflects a broader trend, one that predates the U22 Initiative. Speaking to Conor Walsh in 2023, Columbus Crew Technical Director Marc Nicholls outlined it plainly.

“I’ve been looking at our strategy here in Columbus, and at the [Homegrown] players that have recently gone to Europe as sales,” Nicholls explained. “They’ve played 2,200 minutes in MLS by the age of 20. They haven’t hung around too long in second teams, [earning] maybe as many as 20 appearances. And they [are] sold at about the age of 19.”

That trajectory helps explain why the proportion of domestic U22s remains small. The initiative was designed to help clubs mask raises for young domestic players on the cap, but the league’s top Homegrowns (and, to a lesser extent, SuperDraft picks) are often transferred before an extension can occur.

Take Caleb Wiley, for example. Signed to a Homegrown deal in January 2022, he was transferred for a reported $11 million last summer, one and a half years before his guaranteed contract was set to expire. Obed Vargas, meanwhile, continues to outperform his expiring Homegrown contract, yet with this summer’s Club World Cup the ideal shop window, it seems increasingly unlikely he’ll remain in Seattle long enough to receive a raise — and with it, a U22 tag.

Still, some clubs have chosen to focus their U22 efforts on domestic players, with this year’s Colorado Rapids an example. Homegrown Cole Bassett occupies one of their three slots, with the other two filled by Ted Ku-DiPietro and Josh Atencio — academy products of D.C. United and the Seattle Sounders, respectively.

But, to bring it back to a previous point, there’s a reason D.C. and Seattle were willing to move Ku-DiPietro and Atencio within the league. There’s a reason neither of Bassett’s loans to the Netherlands led to a permanent move, just as there’s a reason Sam Vines, once a Homegrown and U22, returned to Colorado after just two and a half years overseas. These are solid, starting-caliber MLS players, but without elite upside, they’re unlikely to command significant fees abroad. Scan the list of domestic U22s, and you’ll find that most fall into this category.

Therein lies the tradeoff. The nature of the business limits the pool of viable domestic U22s, so clubs that use those slots on Homegrowns — often in their 20s when signing extensions — are prioritizing on-field consistency over future value. By contrast, international acquisitions, especially younger ones, offer greater potential returns but come with the risk of a high miss rate. The most successful approaches hedge that risk with roster depth, ensuring that a swing for upside doesn’t compromise the floor.

FC Cincinnati exemplifies this approach. In January, the club added Paraguayan center back Gilberto Flores as a U22 Initiative player, introducing him to a positional group that included three TAM players in Teenage Hadebe, Matt Miazga, and Miles Robinson, plus veteran Nick Hagglund. Factor in DeAndre Yedlin and Alvas Powell, both of whom can fill in centrally, and Flores didn’t have to hit the ground running; the floor was stable.

The Garys’ approach is more interesting when viewed through a broader lens. By adopting the U22 Initiative Player Model (i.e., 2/4/2 — two DPs, four U22s, and up to $2 million in GAM), as Cincinnati did this year, it appears a club can accommodate one additional TAM player compared to those that opt for the DP Model (i.e., 3/3 — three DPs and three U22s):

In other words, the U22 model allows clubs to absorb the risk of an additional U22 signing, knowing they have the cap flexibility to balance it with stability.

Bet on upside. Insulate the downside.

That’s the model.

In reality, it was a more nuanced approach. For each year from 2021 to 2024, I calculated the number of days from 1) the season’s start to the summer transfer window’s close, and 2) the window’s close to the regular season’s end. I divided those values to obtain a ratio for each season, averaging them to arrive at 2.05. Multiplying a player’s first-year minutes by that value produced his prorated total.

Solid, informative work. Thanks for the work that went into this post.